DOS Announces Temporary Pause on Certain Visas for Nationals of 75 Countries Based on Unfounded Concerns That They Will Seek Public Benefits

On January 14, 2026, the Department of State (DOS) announced a temporary pause on the issuance of immigrant visas (green cards from overseas) for nationals of 75 countries, effective January 21, 2026. DOS said this pause is for the government to review how immigrant visa applicants are evaluated under the “public charge” rules. In announcing this review, the government has indicated it wants stricter standards to prevent new immigrants from receiving any public support.

This policy applies only to immigrant visas (green card processing through a U.S. embassy or consulate) for applicants who are:

- Nationals of one of the 75 countries identified by DOS, and

- Applying for an immigrant visa abroad (not adjustment of status in the United States).

The affected countries include Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belarus, Belize, Bhutan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Burma, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dominica, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, The Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyz Republic, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Pakistan, Republic of the Congo, Russia, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, and Yemen.

Applicants from these countries may attend their visa interviews, but their immigrant visas will not be issued for the time being, unless a limited exception applies. A dual national applying with a valid passport of a country that is not listed above is exempt from this pause. No immigrant visas have been revoked as part of this guidance.

Cyrus Mehta told Law360 “it boggles the mind” that the administration would ban immigrant visas for nearly half the world based on “mere speculation” that those immigrants would come to rely on public benefits.

“Most new immigrants are not even eligible for benefits, and their admission as immigrants is conditioned by legally binding affidavits of support from their sponsors who have met the income requirements,” Mehta said.

It is also hard to imagine that immigrants from Kuwait, Kazakhstan or Uruguay will be lining up for benefits when they immigrate to the US. Those immigrating through a relative who is a US citizen or permanent resident must also be sponsored through an affidavit of support where the sponsor must be able to demonstrate an income that is 125% over the poverty line based on the size of the family being sponsored. Those immigrating through employment based on a labor certification must be promised a salary that is equal to or greater than the prevailing wage in the occupation through which they have been sponsored or through an investment in the amount of $800,000 to $1,050,000.

The American Immigration Council has stated in a blog post that after obtaining a green card, eligible immigrants are subject to a five-year waiting period before they may apply for SNAP (food stamps) assistance, with limited exceptions.

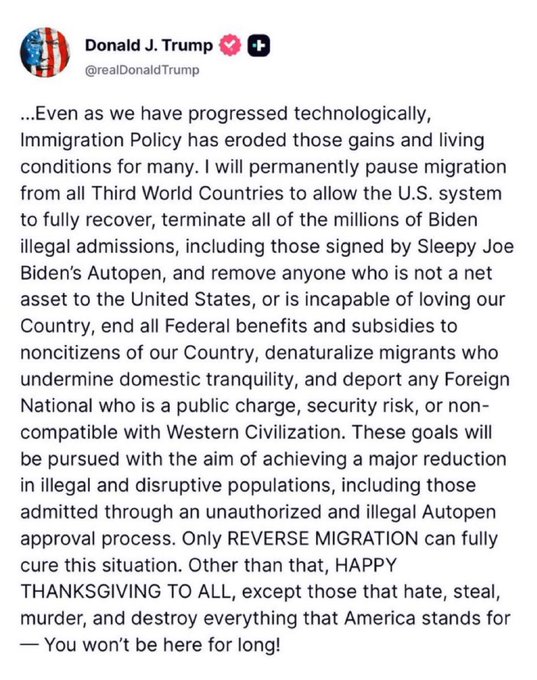

The real reason for the pause is because the Trump administration disfavors immigration to the United States, irrespective of whether it is legal or illegal. Trump’s senior policy advisor in the White House, Stephen Miller, has demonstrated xenophobic and racist views towards immigrants. He has admired the National Origins Act of 1924, which provided for an annual limit of 150,000 Europeans, a complete prohibition on Japanese immigration and which preserved the already existing racial and ethnic status quo of the United States. This law rejected George Washington’s view that the United States should ever be “an asylum to the oppressed and the needy of the earth.”

The State Department’s pause on immigrant visas to nationals of 75 countries under the pretext that they will receive public benefits is a lie. The real reason for the pause, which follows a travel ban on nationals of 39 countries, is to drastically restrict immigration to the US. The Trump administration through Stephen Miller is achieving a ban on immigration without needing to go through legislation similar to the National Origins Act of 1924. It is doing so through executive fiat pursuant to INA 212(f), which allows the president to suspend the entry of noncitizens who he deems would be detrimental to the United States.

The Trump administration’s blocking of nearly half the world from obtaining immigration visas will be a lost opportunity for the United States. The narrow minded thinking of Trump’s main immigration policy architect, Stephen Miller, prevents him from seeing how these immigrants would contribute to the US through their achievements in science, business, arts and many other fields of endeavor as well as through their desire to work hard to better themselves and their families.