Trump’s Escalating Extreme Immigration Measures Towards Noncitizens in the Wake of the National Guard Member Shootings Will Not Make America Any Safer

In the wake of the tragic shooting of two National Guard members on November 26, 2025, one of whom has succumbed, Trump uses her death as a pretext to go after millions who had nothing to do with this attack. The alleged suspect, Rahmanullah Lakanwal, was paroled into the US from Afghanistan as part of Operation Allies Welcome. This program evacuated and resettled tens of thousands of vulnerable Afghans following the US military withdrawal and the Taliban takeover of the country. Lakanwal applied for political asylum in 2024 and was granted asylum in 2025.

Trump has now cast a shadow on not just Afghans who have come to the US, but on all immigrants including lawful permanent residents and even people who have naturalized. One person’s actions do not at all justify the suspension of immigration benefits for all Afghan nationals and the imposition of draconian immigration restrictions. We should refrain from scapegoating and tainting an entire immigrant community even if Trump is indulging in it. This sort of racial profiling creates uncertainty and fear to Afghans who helped the US military at great risk to their lives. It also does a disservice to noncitizens who have immigrated and are contributing to the US.

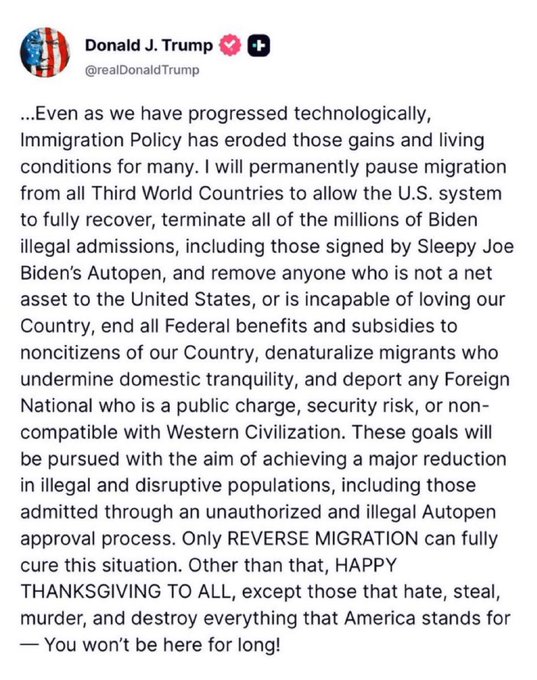

Trump posted this on X in a late night screed on the eve of Thanksgiving:

Trump’s escalating immigration policies in the wake of the shooting include:

- Pausing all asylum decisions

- Stopped issuing visas to people from Afghanistan

- Reviewing green cards issued to people from countries of concern

- Threatening to end migration from third world countries and revoke citizenship from some naturalized citizens

The USCIS is using the countries that were included in the Presidential Proclamation of 6/10/2025 banning their nationals as negative factors when adjudicating benefits. The Proclamation was issued under INA 212(f) which speaks to the entry of aliens that would be detrimental to the interests of the United States. If USCIS relies on INA 212(f) to deny benefits to nationals of these countries who are already in the US, as opposed to those seeking entry into the US, it should not apply as these noncitizens are already in the US. The USCIS’s denial based on one’s country of nationality under the Proclamation could be challenged in court as an inappropriate reliance of INA 212(f). Although the USCIS has broad discretion in adjudicating immigration benefits such as adjustment of status applications, even a blatantly discriminatory policy as denying benefits solely based on one’s nationality might withstand a court challenge. Unfortunately, Congress has precluded challenges to denials of discretionary relief under INA 242(a)(2)(B). So, it may be difficult but not impossible to challenge the USCIS policy as even discretionary denials cannot be blatantly discriminatory.

We have pointed out in early March 2025 that Trump’s policies towards noncitizens were cruel and had no rational justification except to harass and intimidate noncitizens. Just prior to the shootings too, the policy of detaining spouses of US citizens who appear for their adjustment of status interviews at USCIS offices was the unkindest cut of them all. This has been happening at the USICS office in San Diego, and we hope it does not spread to other USCIS offices. The law allows the spouse of a US citizen, along with other immediate relatives of US citizens such as minor children and parents to adjust status in the US under INA 245(a). They are eligible for adjustment of status even if the underlying visitor status has expired. Most of the times the visitor status expires after the adjustment of status application has been filed and is processed at a glacial pace. This is beyond the applicant’s control. Now Trump’s ICE agents with masks appear at an adjustment of status interview to detain the unsuspecting spouse who is all set to adjust status and become a permanent resident. The spouse would still become a permanent resident while in removal proceedings before an Immigration Judge, but what a colossal waste of taxpayer money and needless trauma for the family and kids. The only rationale behind this policy is to inflict cruelty, designed and implemented by either xenophobic or sadistic officials under Trump, or a combination of both, who have no sympathy or compassion towards people who are immigrating to the US legally under the INA and to unite with US citizens they love.

There has been a dark history in the US resulting in the scapegoating of immigrants in times of crisis. A recent example was the restrictions imposed on noncitizens after the September 11, 2001 attack, which included the NSEERS program that resulted in religious, racial and ethnic profiling (see Have We Learned the Lessons of History? World War II Japanese Internment and Today’s Secret Detentions by Stanley Mark, Suzette Brooks Masters and Cyrus D. Mehta). The delicate balance we strive to achieve as a nation between liberty and security inevitably tips towards security, and civil liberties tend to be compromised. While there can never be a justification to go after immigrants in a time of genuine crisis, Trump has manufactured a crisis to justify his administration’s wantonly cruel attacks on immigrants and now will use the shootings of the National Guard members to further restrict immigration.

The need of the hour is to advocate that one person’s bad acts should not taint all immigrants. Indeed, Lakanwal went through extreme vetting measures when they came to the US and applied for political asylum. Before his arrival, Lakanwal worked with the US government, including the CIA as a member of a partner force in Kandahar, Afghanistan, from 2011 until shortly after the US evacuation. Notwithstanding the extreme vetting measures he was subjected to, Lakanwal still shot at the National Guar members, which resulted in the senseless death of Sarah Beckstrom. It appears that Lakanwal got radicalized in the US and no amount of vetting may have prevented his entry into the US. The next shooter may well be a homegrown American who probably has never stepped foot outside the US. It is also worth pointing out that there was no need for Trump to place members of the National Guard in DC and other cities in the first place.

Contrary to Trump’s unhinged post, we must remember that immigrants have played a crucial role in making America great, and restricting immigration based on isolated incidents will only rob the nation of their talents and contributions.

In conclusion, it is imperative that we resist the temptation to respond to tragedy with fear-driven policies. Instead, we should strive for solutions that uphold the values of liberty and justice, ensuring that America – a nation of immigrants – remains a beacon of hope and opportunity for all.