By Stacy Caplow*

Immigration Court, where hundreds of judges daily preside over wrenching decisions, including matters of family separation, detention, and even life and death, is structurally and functionally unsound. Closures during the pandemic, coupled with unprecedented backlogs, low morale, and both procedural and substantive damage inflicted by the Trump Administration, have created a full-fledged crisis. The Court’s critics call for radical reforms. That is unlikely to happen. Instead, the Biden Administration is returning to a go-to, cure-all solution: adding 100 Immigration Court judges and support personnel[1] to help address the backlog that now approaches 1.3 million cases.[2]

No one could oppose effective reform or additional resources. Nor could anyone oppose practical case management changes that do not require legislation and that could expedite and professionalize the practice in Immigration Court. Linked with a more transparent and more inclusive process for selecting Immigration Judges, these changes would make the Immigration Courts more efficient, more accurate and fairer but not at the expense of the compelling humanitarian stakes in the daily work of the Court. Immediate changes that do not require legislation but do require the will to transform the practice and culture of the Court would be a major step forward in improving the experiences and the outcomes in Immigration Court.

I. Changes to the Practices and the Culture of the Immigration Court

Immigration hearings are adversarial. While the stakes are very high and often punitive—removal, ongoing detention, family separation—the proceedings are civil. Yet this court bears little resemblance to typical civil litigation settings in both the pretrial or trial context. Most of the characteristic judicial tools regulating litigation are absent: pretrial discovery, pretrial settlement or status conferences to resolve or narrow issues, rare stipulations, or enforcement tools to require government lawyers to participate in a meaningful way until shortly before the hearing.

Generally, no Trial Attorney [TA] from the Office of the Principal Legal Advisor [OPLA], a division of Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE], the prosecutors in Immigration Court, is assigned to or takes responsibility for a case until a few weeks prior to an individual hearing.[3] If a case is pending for several years, as so many are these days, except in the rare instance, it is impossible to have any kind of substantive discussion in advance about the conduct of the hearing, possible forms of settlement or alternative relief, narrow issues. Stipulations are rare or unhelpfully last minute. There are no enforcement tools that require government attorneys to participate in a meaningful way until shortly before the hearing. This can and should be changed. The Immigration Court can adopt practices familiar in civil and criminal tribunals around the country. Common litigation management tools could expedite and rationalize Immigration Court proceedings.

1. Assign Trial Attorneys to Cases Promptly

A TA should be assigned to review a case at the earliest possible time following the initial Master Calendar appearance where pleadings are entered. At a minimum, a TA should be assigned at the request any Respondent who wants to discuss a case regardless of when the hearing is scheduled. The government lawyers in Immigration Court, like prosecutors in any busy court, can handle a caseload without waiting until the last minute to review the claim. In order to foster meaningful discussions, these TA assignments should occur as soon as the respondent has completed her evidentiary filings.

The positive impact of a prompt TA assignment system will benefit everyone—Respondents, TAs, and the IJs. For example, although many cases require a credibility finding based on in-person testimony, some claims simply do not. If there is no basis for doubting credibility in light of the evidence, and the law is clear, a one, two or three-year wait for a decision is unconscionable. Under the current system, the TA does not review the submissions until shortly before the hearing. Faced with cases in which credibility is not an issue, more often than not, the TA does not seriously contest the facts or the eligibility for relief once she has reviewed the submissions. This results in half-hearted cross-examination, if there is any at all, and a quick grant of relief without opposition. Unfortunately, this happens only after years of delay and anxiety as well as extensive preparation often requiring logistical headaches and inconveniences to witnesses. Earlier, thorough case assessment could avoid the stress to Respondents of a life on hold, could result in fewer or more focused hearings, and could accomplish timeliness and efficiency goals of EOIR.

2. Require Pre-Hearing Conferences

The EOIR Practice Manual provides for a Pre-Hearing Conference.[4] This tool, commonplace in other kinds of courts, is rarely used. Neither Immigration Judges nor TAs routinely invite or encourage pre-hearing conferences. Following the lead of many civil and criminal courts, there should be a regularly scheduled status conference in every case upon a simple request from either party, conducted as expeditiously as possible after the pleadings at the Master Calendar. This could achieve great efficiencies and fairer outcomes.

A mandatory pre-hearing conference would necessitate assigning an individual ICE Trial Attorney to a case well in advance of the hearing. For an effective conference, a Respondent’s lawyer would generally need to submit evidence and even a memorandum of law. A process similar to a summary judgment motion might result. If the Trial Attorney concedes that there are no factual disputes or lack of credibility, the judge could decide the legal basis for relief. This procedure might require an abbreviated hearing, an oral argument, or could be decided on written submissions.

A few prototypical cases illustrate how this might work. Imagine an asylum seeker who has suffered or who has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of sexual orientation who comes from a country whose homophobic laws and oppression of people who are LGBTQ are undisputed. If the asylum seeker is credible, well settled law would surely warrant a granted of asylum. Or suppose a woman who was subjected to genital circumcision has medical records confirming this condition. Again, under well-settled law she is likely to be granted asylum. Or a one-year filing deadline bar could be resolved without the need for testimony based on written submissions. These issues could be resolved at a pre-hearing conference. Another set of cases might involve requests for Cancellation of Removal. The pre-hearing conference could conclude that objective evidence satisfies most of the statutory factors. This could narrow the case so that the Immigration Judge would only hear evidence relevant to the hardship determination. If the Trial Attorney reviewed the evidence and conceded that the hardship standard had been satisfied, this could eliminate the need for a hearing altogether.

Immigrants and their advocates shoulder the burden of multi-year delays and suffer from the resulting uncertainty and angst. Meanwhile, they build lives despite their unpredictable future, increasing the harsh impact of eventual deportation. During the interval, immigration advocates’ caseloads multiply. Years later, when a hearing is finally held, the consequences of delay are substantial. Court submissions need updating. Legal claims may be affected by changes in the law. Witnesses may be unavailable. Memories may fade. The is particularly harsh for asylum seekers whose credibility is at the heart of any immigration hearing[5] but whose trauma may have affected their ability to recall events, particularly the persecution they would prefer to forget. Accelerating resolution through pre-hearing processes following a full presentation of the claim by the Respondent and a full review of the evidence by the government would divert cases from the court’s hearing dockets.

A serious and sincere discussion of the claims and the evidence might resolve cases more expeditiously. Relief could be granted without a hearing. In some instances, TAs could choose to terminate the proceedings through an exercise of prosecutorial discretion. Good case management, effective communication, and open-mindedness are imperative to making the system work more smoothly and more quickly.

3. Enforce the Practice Manual Equably

After years without any standardized practices, the EOIR published a Practice Manual.[6] This guidance was a welcome development. On its face, it appears to govern all aspects of practice neutrally. A closer reading of the Manuel, however, reveals how one-sided these rules and the practice they govern really are. The everyday reality is even more blatantly lopsided because only Respondents’ attorneys actually do the work that the Manual regulates. The power imbalance between the parties and the close relations between the immigration bench and the prosecutors is embedded in the contents, language and impact of the Manual

In most cases before IJs the burden of proof to secure relief is on the Respondent, once removability is established.[7] This means that Respondents, represented in only about 60% of all cases,[8] submit all of the evidence to support their application for relief. In the Manual, there are detailed rules relating to filings, motions and the conduct of hearings down to the types of tabs, cover sheets, identifiers for motions, cover pages, tables of contents, proof of service, witness lists and hole-punching. Submissions must be filed and served at least 30 days in advance of the hearing (up from 15 in a prior version of the Manual)

Since government lawyers rarely submit any evidence other than proof of removability if the Respondent does not concede, none of these rules affect their workload. On the rare occasion that the ICE lawyers do file a proposed exhibit, they often do so on the day of the hearing—with impunity since the IJs permit this. In a typical court, flagrant disobedience of the rules would be sanctioned without prejudice to the other party. More typically a Hobson’s choice is given to the Respondent: accept the poor service or postpone the case. These days, postponement can mean years. The Respondent, anxious and prepared for that day’s testimony, is likely to opt for the former letting the government ignore the rules with the IJs permission.

This is an example of how IJs could behave more forcefully—preclude the evidence. Or cite the government for contempt in egregious cases. Instead, a tolerance of lazy lawyering only inspires even less compliance with the rules

4. Encourage Prosecutorial Discretion as a Case Management Tool

Resolving a case through an exercise of prosecutorial discretion [PD] is another tool available to, but rarely employed by, the government. IJs cannot force Trial Attorneys to take certain actions relating to the merits of a case, but they can review the evidence in a pre-trial conference and make a strong suggestion about the best resolution.

The May 2021 Interim Guidance to OPLA Attorneys Regarding Civil Immigration Enforcement and Removal Policies and Priorities is a vehicle for re-evaluating prosecutorial discretion [PD] as part of the holistic case management reforms that will benefit the TAs. the Immigration Court and the Respondents.[9] The Interim Guidance reestablishes priorities and encourages a resuscitation of vigorous prosecutorial discretion. The guidance gives express permission to the Trial Attorneys to consider prosecutorial discretion even in the absence of a request.[10] Its reference to “mutual interest” strives to break down the adversarial barriers that obstruct judiciously exercised discretion and encourages shared problem-solving.

Some OPLA offices have established protocols for submitting requests for prosecutorial discretion. It is too early to tell whether this change in policy will result in a change in culture in the field. In the past, requests were not very successful despite encouraging guidelines and priorities.[11] But even if the Trial Attorneys do not take initiative, at the very least, there is a structure in which to engage in serious discussions about the direction of a case on the court’s docket. While the ultimate exercise of discretion belongs exclusively to the TAs, IJs could and should identify and encourage active consideration of appropriate cases for PD at a Pre-Hearing Conference.

5. Apply Disciplinary Rules to Government Lawyers as well as Immigration Advocates

Lawyer disciplinary rules must be applied equally to ICE attorneys as well as attorneys for Respondents. This recommendation may seem obvious. Yet, the 2018 Policy Guidance promulgated by the EOIR raised serious concerns.[12] It established policies and procedures for reporting ineffective assistance of counsel or other violations of rules of professional conduct identified by the EOIR itself. Of course, protecting immigrants against unscrupulous or incompetent lawyers is a worthy goal. But these disciplinary rules apply only to immigrant advocates and not government lawyers.[13] EOIR should promptly issue equivalent guidance that applies to ICE attorneys who might commit ethical violations. In the absence of attempts by EOIR to be evenhanded, the 2018 policy guidance is a troubling example of bias within the court system.

6. Be Attentive to Professional Standards in the Courtroom

All of these practical manifestations of the imbalance of power—the reluctance to regulate, sanction or discipline—and the very environment of the courtroom expose the cozy connection between the immigration bench and the prosecution and destroy any fiction of independence. IJs preside in courts in which former colleagues (perhaps friends) appear. They chitchat with the government lawyers while Respondents sit in the room, often in a cone of incomprehension. The appearance if not the reality of this relationship is visible to any observer. The integrity and objectivity of the court is seriously undermined by these everyday departures from appropriate courtroom conduct. The obvious and easy remedy for this appearance of partiality inferred from the comradery between the prosecutor and the judge would be a change in atmosphere to elevate the inside of these courtrooms to the same degree of dignity and seriousness that all courtrooms should possess.

II. Changes to the Selection Process of Immigration Court Judges

To transform the present obstacles to effective judicial performance, remove the damaging management directives of the former administration. As so many commentators already have suggested, roll back the heavy-handed Attorney General imposed operating guidelines relating to case management to restore a system of logical adjudication priorities[14] and remove the Damoclesean sword of quantitative performance metrics or quotas which only encourage hasty outcomes that devalue the stakes involved in most hearings. These steps require only will, not legislation or rule making. While a return to the old normal will not fully address the structural capture of this court by the Department of Justice [DOJ] and the widely divergent outcomes between courts,[15] restoring decision making to IJs will improve morale and incentivize judges to be independent thinkers without fear of interference or reprisals.[16]

The Attorney General recently took significant steps to reverse many of the more controversial and harmful administrative policies inflicted by the prior administration that limit the ability of Immigration Judges to decide their cases carefully and fairly.[17] But more can be done.

Changes to the eligibility criteria and the selection process for Immigration Judges also would make a difference both to how the Court operates and how its integrity is perceived by the people appearing before it and by the public.

1. The Past Decade of Immigration Court Growth

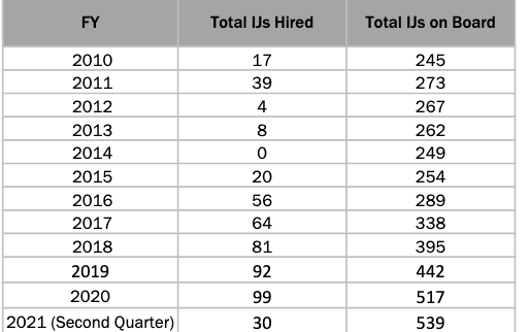

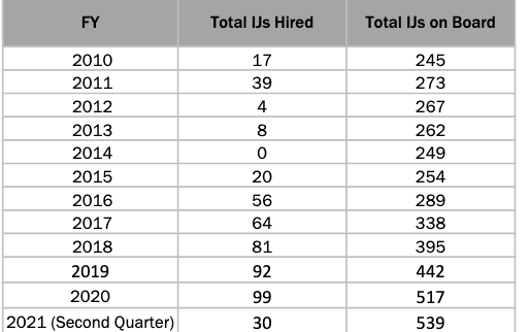

Injecting new resources into the Immigration Courts is a common prescription for a system that is overloaded, backlogged, and inefficient. This approach seems sensible, and it has indeed been tried but without much success. Between 2017 and the end of 2020 more than 330 judges were added to the ranks in an effort to reduce the enormous backlog. The table below shows the exponential growth in judges.

Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics[18]

Over that same four-year period, almost 100 courtrooms were added, totaling 474 at the end of 2020.[19] Now, approximately 535 immigration judges preside over 68 immigration courts and three adjudications centers.[20]

Despite the infusion of resources, waiting times have grown to an average of 54 months.[21] Although the Executive Office of Immigration Review asserts that, “The timely and efficient conclusion of cases serves the national interest,”[22] today many hearings are adjourned for as long as two or three years. Swift and certain justice after a full and fair removal proceeding eludes most people.

While some of this eye-popping number of pending matters is attributable to the influx of asylum-seekers at the southern border,[23] Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE] also has been filing new removal cases.[24] In addition, the pandemic shut most of the courts for more than a year. These external forces have been intensified pressures, but they are not the root causes of the Court’s dysfunction. Adding more judges will not solve the well-recognized structural defects of the court itself.

An immigration bench that has been populated to serve political goals lacks genuine independence and is subject to political branch dictates.[25] The Trump Department of Justice only further diminished judicial independence by imposing performance metrics,[26] limiting the exercise of discretion,[27] litigating to decertify the judges’ union,[28] muzzling individual judges,[29] and radically changing longstanding legal principles.[30] On its own website, the stature of this tribunal is degraded to “quasi-judicial,” dropping the pretense of independence and reducing its stature.[31]

The breakdown of the court is also attributable to recent mismanagement decisions and its almost total departure from normal litigation practices that prevents judges from supervising their caseloads and promptly presiding over life-altering deportation proceedings. Administrative inefficiencies that have longed plagued this court only worsened under the policies adopted by the four-year, multi-faceted Trump assault on immigration. Old cases languished while new cases poured in.

In light of this grim reality, the time has come to rethink of some embedded assumptions and practices, particularly those that do not have to wait for structural court reform.

2. Surveying the Newly Appointed Immigration Judges

The job of Immigration Judge, as one IJ famously said, consists of hearing “death penalty cases in a traffic court setting.[32] Immigration Court needs to be staffed by experienced judges committed to applying the law with both rigor and compassion. Immigration Judges need to be able to use the tools that judges normally employ in other settings to administer their courts effectively. Knowledgeable, fair-minded, even-tempered, confident and courageous judges should be the norm.

The following collective profile of the newest IJs has been noted widely but some aspects deserve a bit more detailed attention because they call into question whether this goal can be achieved if past practices are simply replicated as more IJs are appointed.

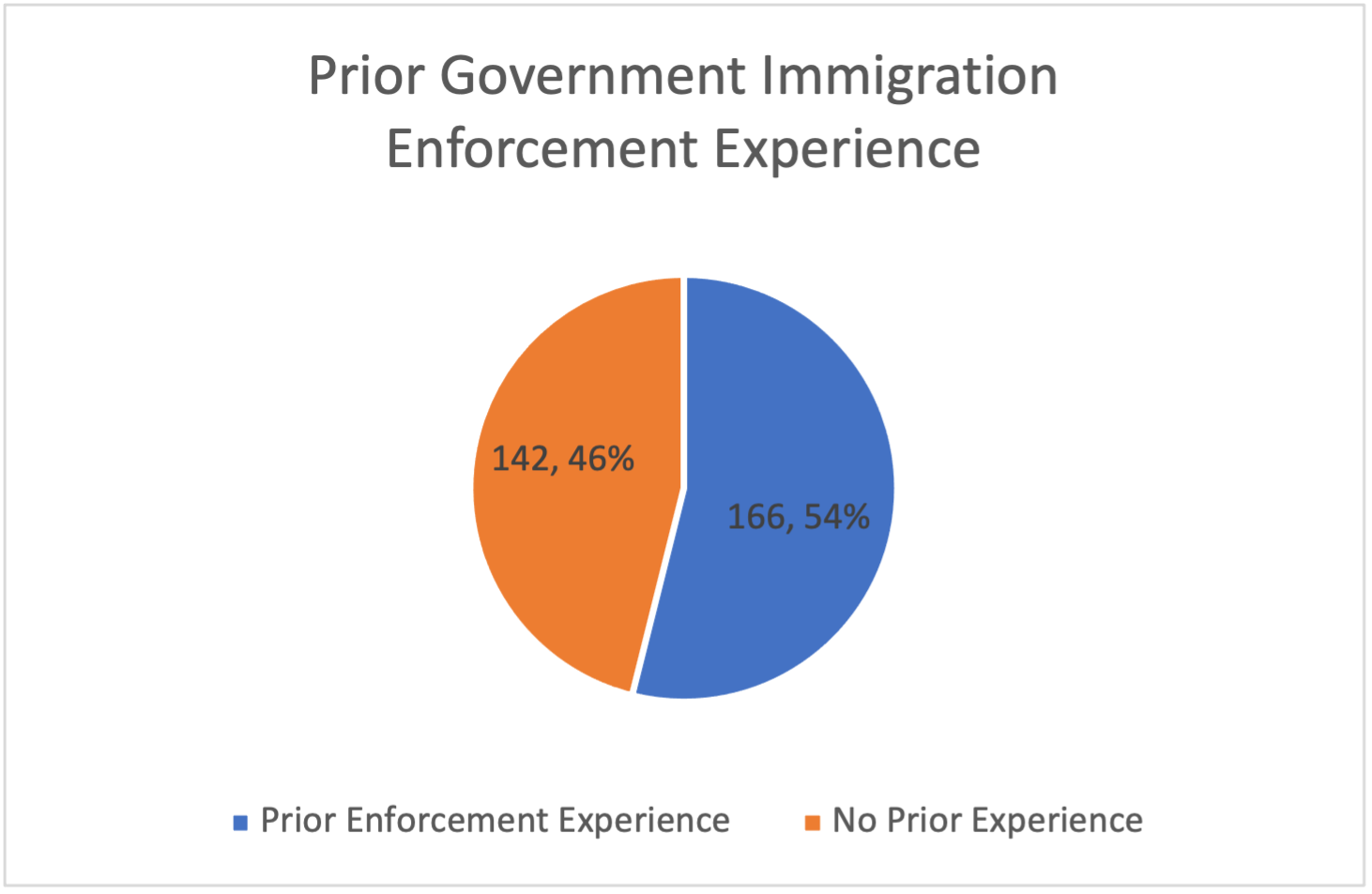

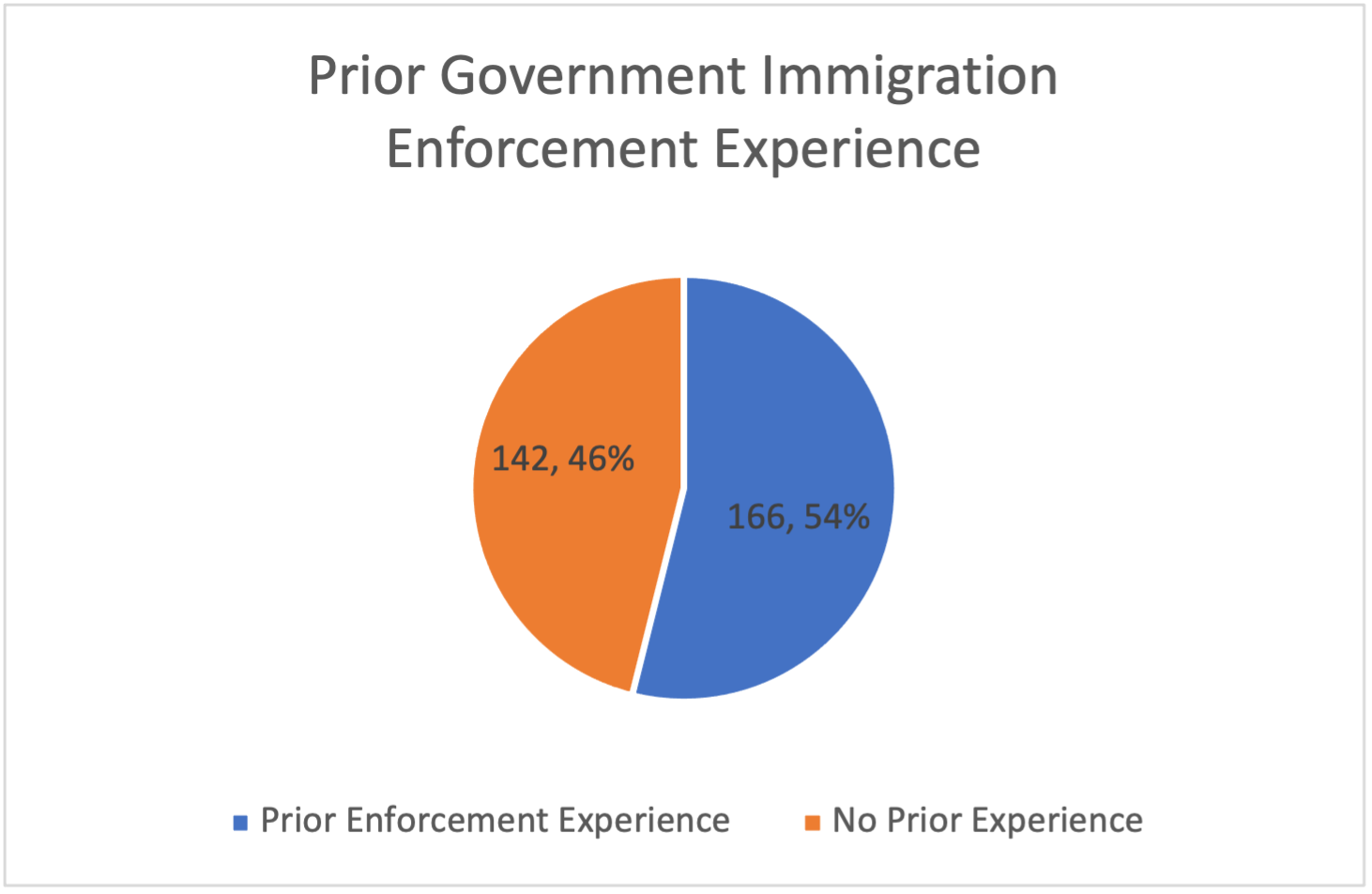

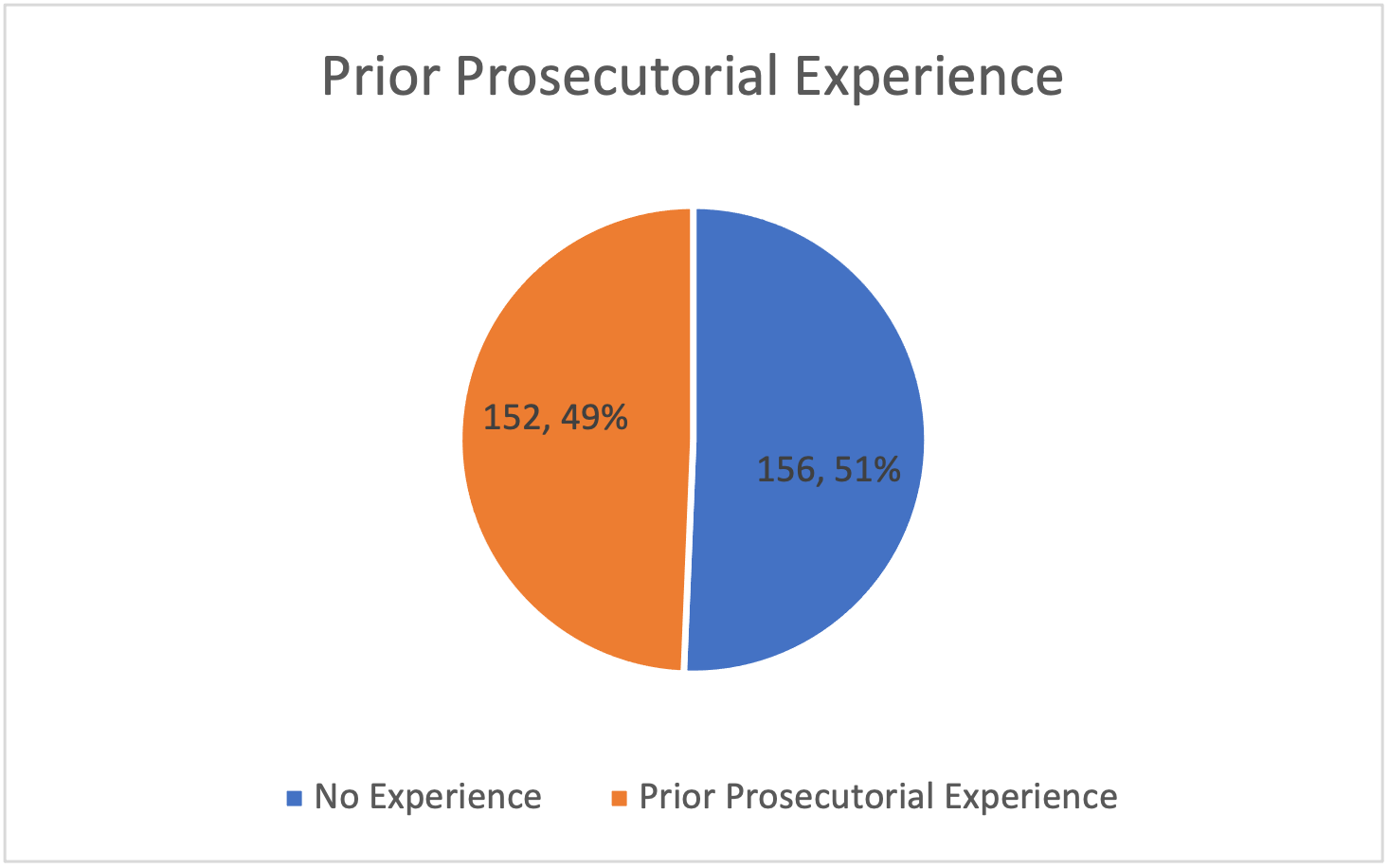

a. Government Enforcement Background

From 2017 to 2020, the Department of Justice hired 166 judges who were drawn predominantly from current or former employees of one or more government-side immigration prosecution, enforcement or related agencies.[33] Filling the bench with lawyers from this career path is not new, or particularly surprising, since these are candidates who actually do have a deep knowledge of the law and a familiarity with the court. But a career in enforcement risks distorting objectivity and impartiality.

There is, however, a striking imbalance among the IJs with considerable immigration practice backgrounds. A review of their biographies reveals that only a handful—about 10 or 11—worked in either private practice or public interest organizations representing immigrants. Thus, one of the two obvious source of experienced immigration attorneys—immigrant advocates—is barely represented.

Another conclusion that these numbers forcefully imply is that not only are government-side lawyers overly represented but, even when the few former immigrant advocates are added to this group, close to half of new IJs appear to have no discernable knowledge of immigration law or experience in immigration practice.[34]

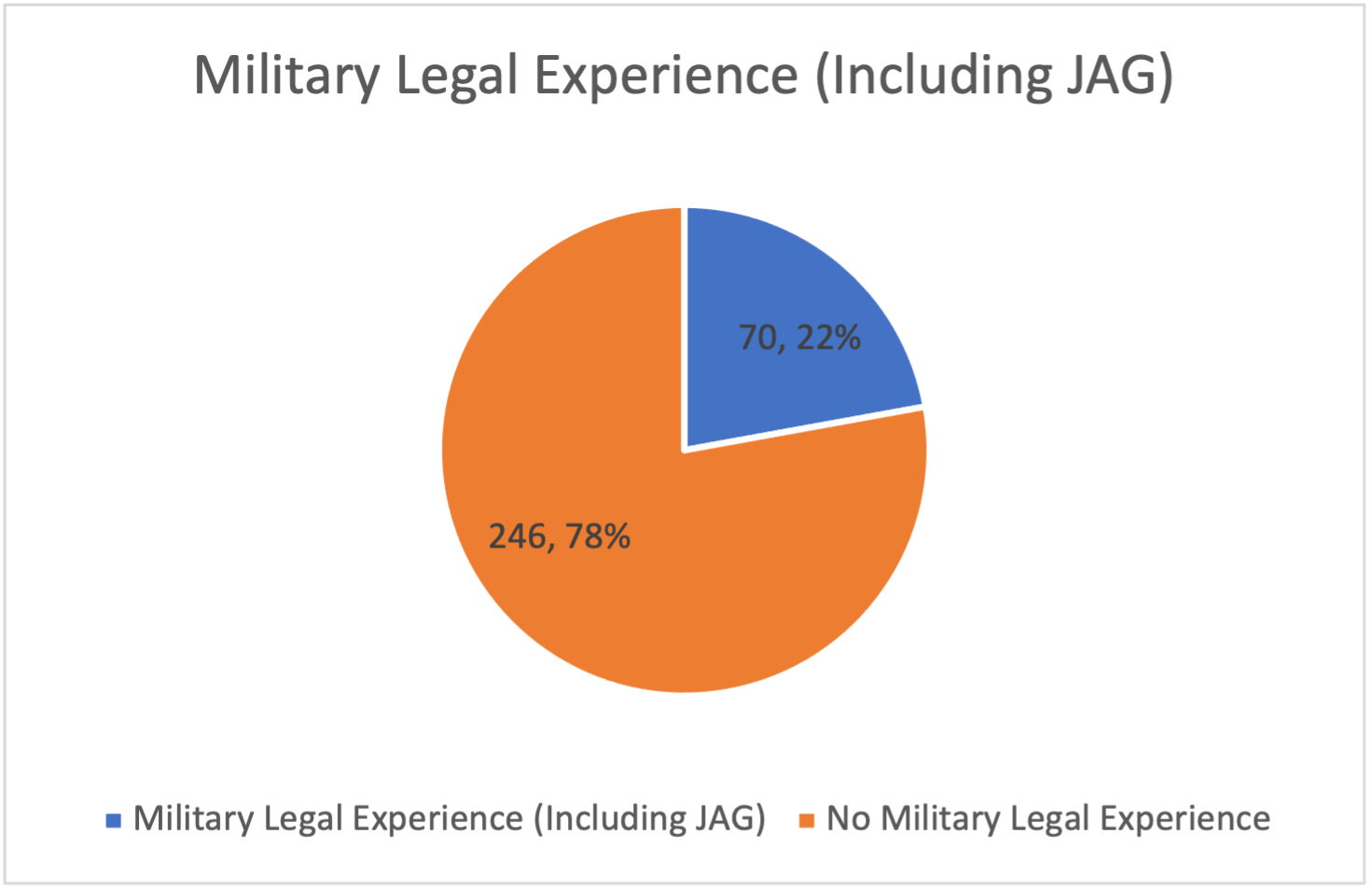

Lawyers with government immigration careers are not the only former law enforcement employees sitting on the Immigration Court bench.

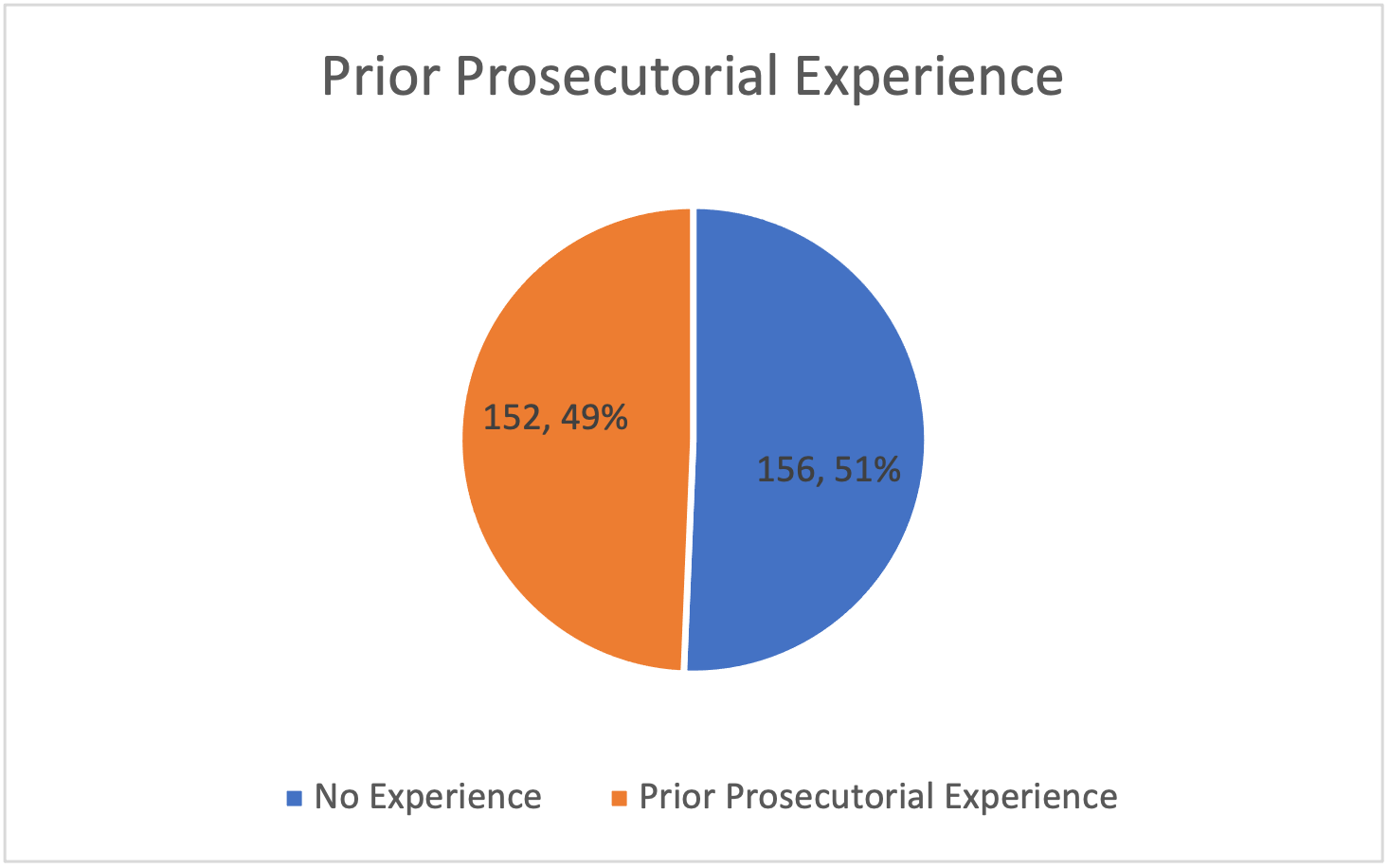

- Fifty-four percent of new IJs’ credentials include past positions as either federal and/or state prosecutors, or both.

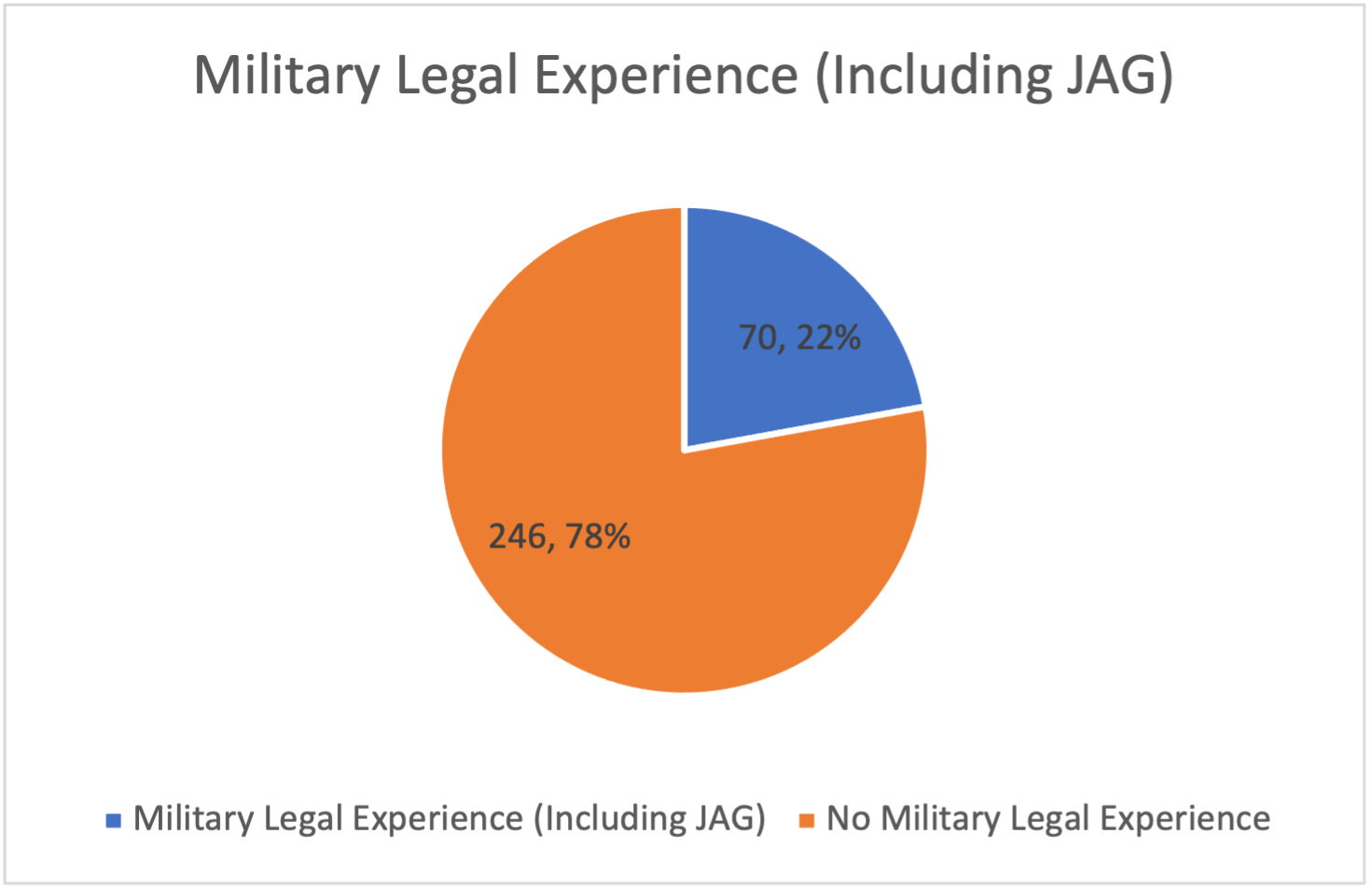

- Many have military records (often in combination with prosecutorial pasts), an advantage in the selection process. But they report no immigration law experience.

Many individual biographies include a combination of these experiences—e.g., government enforcement jobs, prior prosecutorial positions and military service. At the risk of overgeneralizing, there are many common characteristics in these backgrounds that could discourage independence, critical or creative thinking, as well as produce intolerance for inefficiency, aggressive advocacy or other challenges to authority.

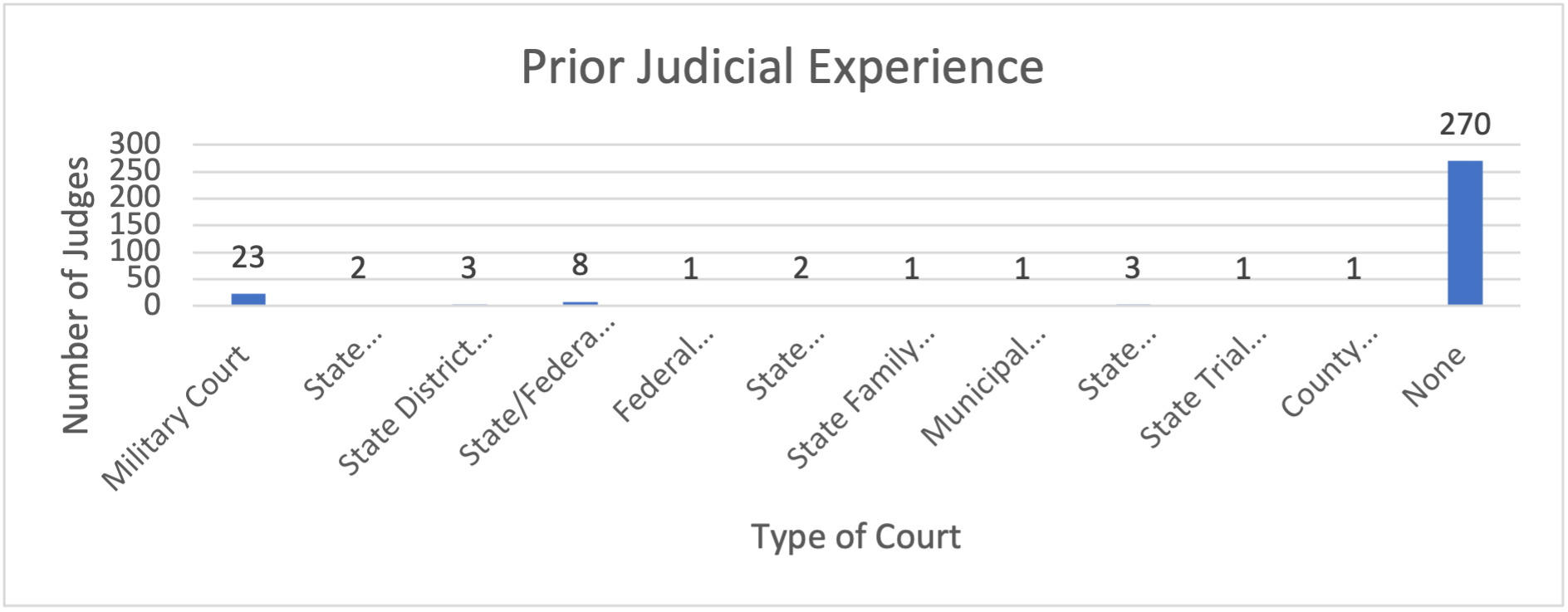

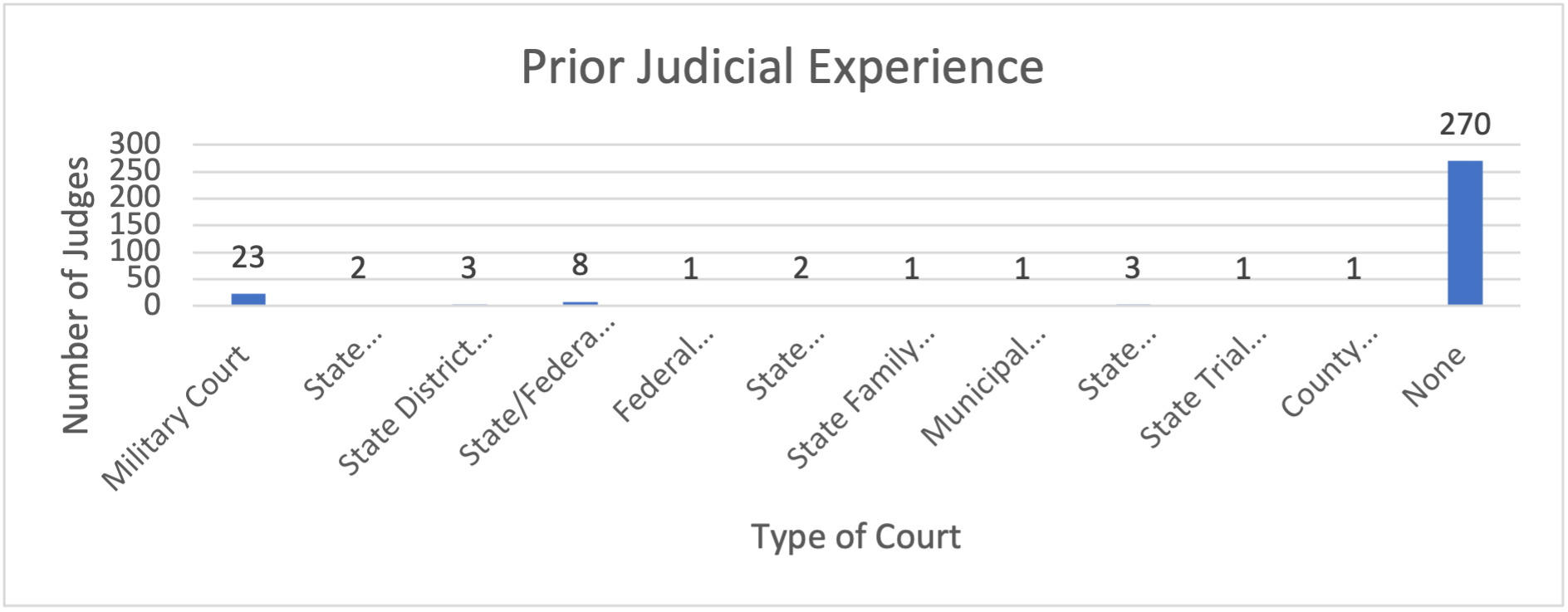

b. Judicial Experience

Prior judicial experience would seem to be a plus but only a handful of the new IJs, 46, have sat on any bench, all of which are state-level tribunals or courts with no obvious immigration jurisdiction.

The haste to seat these judges and put them to work with minimal training[35] and little opportunity for ongoing mentorship by experienced judges, only incentivizes them to rush through hearings, and predisposes them to deny applications accompanied by incomplete or sloppy reasoning.[36] Just as more judges are being added, veteran judges are leaving the bench, some in reaction to the new pressures to perform.[37] As witnesses to the degrading of the court, the increasingly active and expanding Round Table of Former Immigration Judges has been a vocal critics both before Congress and as amicus curiae.[38]

c. Legal Experience

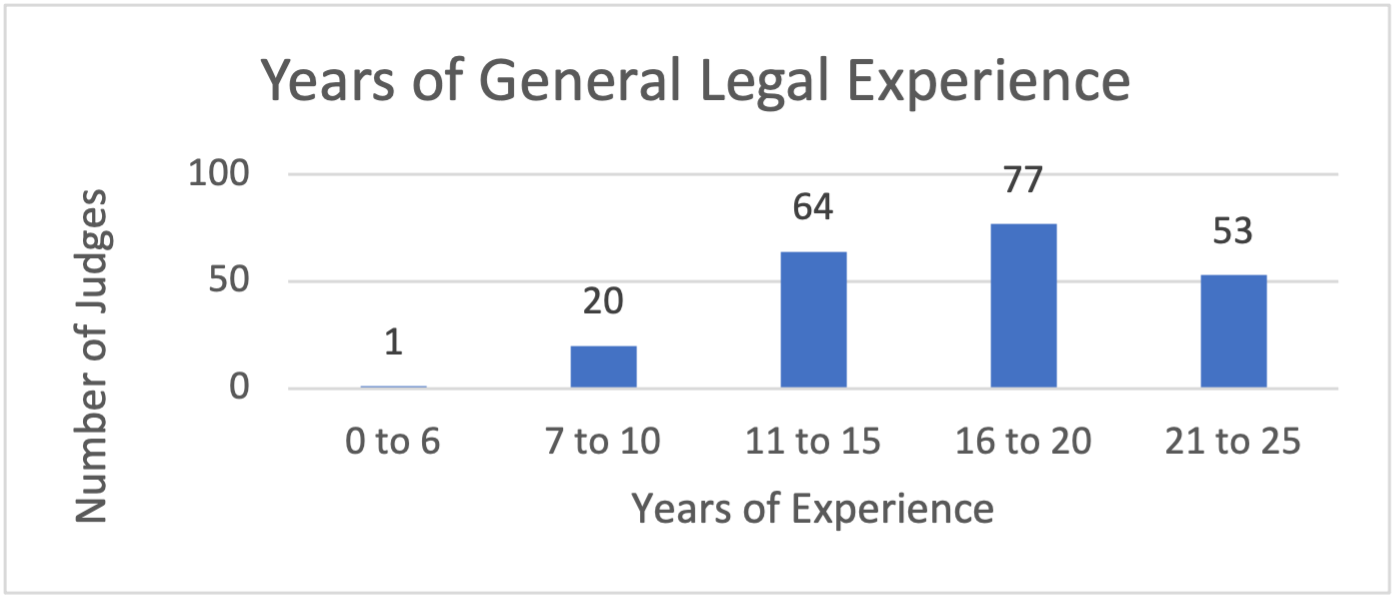

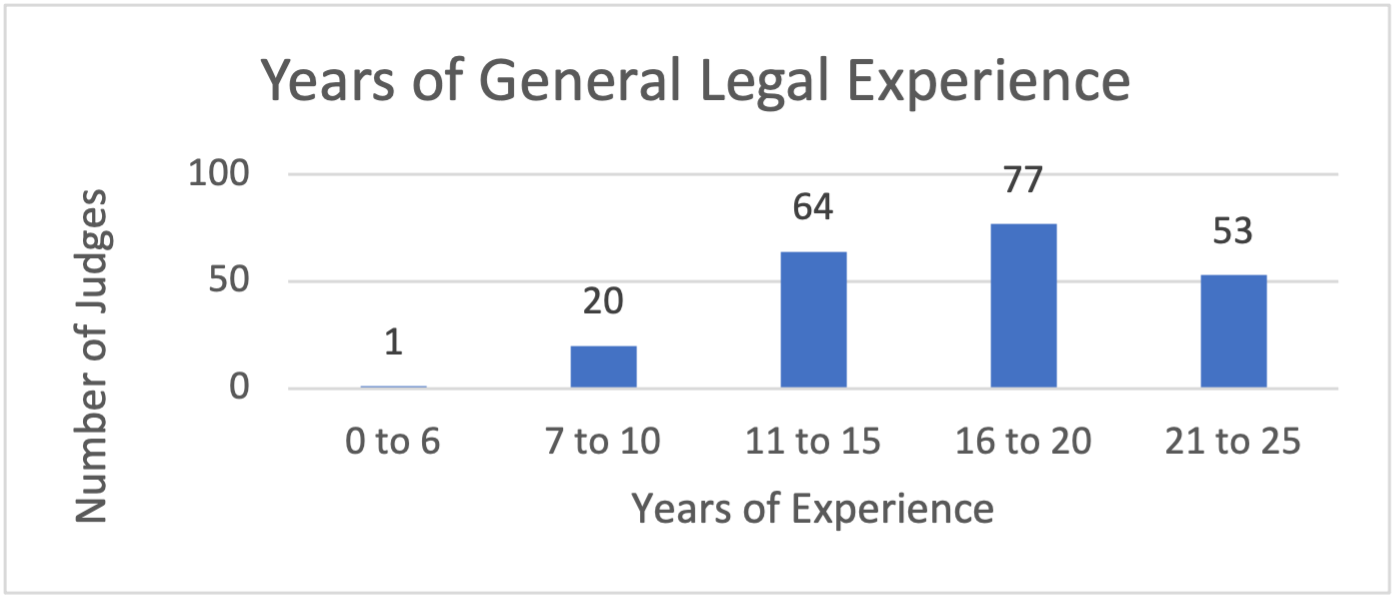

Generally, ascent to the judiciary occurs after a lawyer acquires expertise in a legal field, and demonstrates maturity, judgment and capacity. Knowledge of the law, an even temperament, impartiality and the ability to make reasoned decisions are the basic qualities associated with judging. Lawyers usually requires years of legal experience to gain and deepen these qualities. The requirement of seven years post-bar admission seems quite minimal.

The survey showed that most new IJs do have more than the minimum amount of

experience. But, when their years in practice is seen are measured by the kind of experience the majority of these seasoned lawyers have—government enforcement—it is fair to conclude that their often extensive and formative careers opposing or obstructing relief and challenging credibility have shaped their judicial outlook.

d. Bias in Results

The opaque selection process seems to yield judges with questionable qualifications and possible biases. The data tends to confirm the prediction that the newly appointed IJs with these credentials are granting fewer requests for asylum relief.[39] According to EOIR’s own statistics, the denial rate since 2018 increased from a range of 20-32%) to continuously increasing ranges of 31.75% to 54.53% by 2020.[40]

Looking at the list of individual IJs the change is even more obvious. Between 2013 and 2018, 58 judges denied asylum more than 90% of the time, and 69 judges denied asylum between 80-90% of the time.[41] Over the five-year period 2015-2020, the number of IJs who denied asylum more than 90% of the time rose to 109 and the number denying asylum between 80-90% of the time rose to 111.[42] While some toughening of legal standards imposed by the prior administration might account for a portion of this upsurge in denials,[43] the coincidence between these dramatic numbers and the infusion of new IJs appointed by the Trump Department of Justice is hard to ignore.

e. A Better Judicial Selection Process

An infusion of new personnel in the near future provides an opportunity to look closely at and reform the appointment process of Immigration Judges to make it less vulnerable to political influences. By many accounts, it was intensely politicized over the past four years. Appointment to the court is governed by the Department of Justice, allowing the country’s chief prosecutor to unilaterally advance a frequently biased agenda.[44] This undeniable conflict is nothing new but it demeans the integrity of the bench. Even worse, the opaqueness of the selection process shields an agenda that is suspect, based on the profile of the IJs appointed over the past four years.[45]

A cleaner, more transparent merit selection process, typical of most judicial systems, would enhance the reputation of the Court and might attract a more diverse applicant pool through a recruitment process that is attractive to a wider range of applicants. The work is very demanding, but it pays well.[46]

In addition, the criteria for the job, are now absurdly undemanding. Aside from a law degree and licensure in any U.S. jurisdiction, an applicant must have

[A] full seven (7) years of post-bar experience as a licensed attorney preparing for, participating in, and/or appealing formal hearings or trials involving litigation and/or administrative law at the Federal, State or local level. Qualifying litigation experience involves cases in which a complaint was filed with a court, or a charging document (e.g., indictment or information) was issued by a court, a grand jury, or appropriate military authority. Qualifying administrative law experience involves cases in which a formal procedure was initiated by a governmental administrative body.[47]

Knowledge of or experience in immigration law is not an expressed job qualification although it may be an advantage.

Without the need for legislative reform, the Department of Justice and the EOIR could improve the perception and reality of the Immigration Court selection process. Simple improvements include the following steps: 1) elevating the selection standards to require more than 7 years’ experience and more direct knowledge of immigration law; 2) assuring a neutral merit selection process that incentivizes. applications from immigrant advocates; 3) opening the selection process for more public input; 5) improving training and oversight that emphasizes competence more than productivity; 6) restoring morale by recognizing and respecting the responsibility placed on IJs and treating them not as employees but as judicial officers; and 7) overseeing and questioning the basis for abnormally high denial rates.

III. Conclusion

Is there a life preserver on this sinking ship? Courts reopening following the pandemic are facing an unprecedented backlog with cases already postponed years into the future. The new Administration, in the position to institute real reform to the way business is conducted, has started to steer in a positive direction due to a now shared interest of the Court and ICE to address the burdensome and shameful backlog. This is a potentially defining moment when change may actually happen. Meanwhile, the new administration is articulating goals to ameliorate not only the backlog but to seriously change enforcement priorities. If these two agents of potential change take advantage of the crisis that is affecting everyone involved with the system to work collaboratively with each other and consult sincerely with the immigrant advocates bar and other stakeholders, there may be some hope. To make this happen, a true cultural change must occur at every level. A few small steps have been taken: The EOIR is reacting to the prosecutorial discretion directive but the jury is still out on the buy-in to any kind of genuine reform.[48]

Like a lifeboat, survival depends on a commitment to problem-solving, trust and collaboration until rescue arrives. Someday structural reform may truly reshape the court to enough to eliminate the qualifier quasi. IJs will become full-fledged judges capable of making legally sound decisions in courtrooms where dignity, respect, patience and compassion are the norm without fear of retribution. Give the judges the tools they need to manage their courtrooms and the parties to achieve goals of integrity, efficiency and fairness. Recalibrate the balance between the parties. Recognize the demands of presiding over life-altering matters on their own wellbeing by giving them the resources, the power and the trust to be full-fledged judges.

Until then, directives from the top down are an important start; transformation still depends on change in the field in order to bring this court in conformity with general adjudication norms and practices, as well as to successfully implement the policy instructions that have the potential address the court crisis from the government’s standpoint without sacrificing fairness and humanitarian considerations.

Guest author Professor Stacy Caplow teaches Immigration Law at Brooklyn Law School where she also has co-directed the Safe Harbor Project since 1997.

Footnotes

[1] President Biden’s proposal is part of his overall budget planning, See Letter from Executive Office of the President, Apr. 9, 2021, at 22:

Supports Efforts to Reduce the Immigration Court Backlog. In order to address the nearly 1.3 million outstanding cases before the immigration courts, the discretionary request makes an investment of $891 million, an increase of $157 million or 21 percent over the 2021 enacted level, in the Executive Office for Immigration Review. This funding supports 100 new immigration judges, including support personnel, as well as other efficiency measures to reduce the backlog.

available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/FY2022-Discretionary-Request.pdf. See also Fact Sheet: President Biden Sends Immigration Bill to Congress as Part of His Commitment to Modernize our Immigration System, Jan. 20, 2021, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/fact-sheet-president-biden-sends-immigration-bill-to-congress-as-part-of-his-commitment-to-modernize-our-immigration-system/.

[2] TRAC Immigration, The State of the Immigration Courts: Trump Leaves Biden 1.3 Million Case Backlog in Immigration Courts, available at https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/637// (last visited July 28, 2021). This statistic is complicated and does not fully account for all matters since some have been “inactive” thereby excluded from the final figure. Id. at n. 1. The Executive Office of Immigration Review reports 1,277,152 pending cases as of the first quarter of FY2021 i.e. Dec. 31, 2020. See https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/637/ (last visited July 28, 2021).

[3] “The Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) is the largest legal program in DHS, with over 1,250 attorneys and 290 support personnel. By statute, OPLA serves as the exclusive representative of DHS in immigration removal proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review, litigating all removal cases including those against criminal aliens, terrorists, and human rights abusers.” See https://www.ice.gov/about-ice/opla.

[4] “Pre-hearing conferences are held between the parties and the Immigration Judge to narrow issues, obtain stipulations between the parties, exchange information voluntarily, and otherwise simplify and organize the proceeding.” OCIJ Practice Manual, Sec. 4.18, available at, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/eoir-policy-manual/4/18.

[6] Office of the Chief Immigration Judge, Practice Manuel, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/eoir-policy-manual/part-ii-ocij-practice-manual (updated March 24, 2021).

[7] INA § 240 (c)(4).

[8] Interestingly, while there is general consensus that representation makes a huge difference to positive outcomes, the denial rate for asylum increased12% between 2108 and 2020 notwithstanding representation. Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics Current Representation Rates, available at

https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1062991/download(Date generated April 2021).

[9] John D. Trasivina, U.S. Immigration & Customs and Enforcement, Interim Guidance to OPLA Attorneys Regarding Civil Immigration Enforcement and Removal Policies and Priorities INA § 240 (c)(4)(C), May 27, 2021, available at , https://www.ice.gov/doclib/about/offices/opla/OPLA-immigration-enforcement_interim-guidance.pdf.

[10] Id. at 7-8.

[11] An example of the policies for the exercise of prosecutorial discretion during the Obama administration is the Policy Memorandum Number: 10075.1 issued by John Morton, then Director of ICE entitled Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion Consistent with the Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities of the Agency for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Aliens, June 17, 2011, available at https://www.ice.gov/doclib/secure-communities/pdf/prosecutorial-discretion-memo.pdf.

[12] Internal Reporting of Suspected Ineffective Assistance of Counsel and Professional Misconduct, PM 19-06, Dec. 18, 2018.

[13] AILA Letter to Director James McHenry, February 15, 2019 (AILA Doc. No. 192159 (on file with author).

[14] See, e.g., Recommendations for DOJ and EOIR Leadership To Systematically Remove Non-Priority Cases from the Immigration Court Backlog, AILA Doc. No. 21050301

(posted 5/3/2021), available at file:///Users/stacycaplow/Downloads/21050301.pdf.

[15] Philip G. Schrag, Andrew I. Schoenholtz and Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Refugee Roulette. (2011). NEED FULL CITE For example, in the Atlanta Immigration Court, every judge’s denial rate exceeds 90% in contrast to the New York Immigration Court where 29 judges deny in less than 30% of cases. TRAC Immigration, Judge-by-Judge Asylum Decisions in Immigration Courts

FY 2015-2020, available at https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/judge2020/denialrates.html.

[16] This essay does not address the longstanding arguments advanced for an independent Article I Court. For a selection of perspectives on that see, e.g., Dana Leigh Marks, An Urgent Priority: Why Congress Should Establish an Article I Immigration Court, 13-1 Bender’s Immig. Bull. 3, 5 (2008) (the author is an Immigration Judge); Maurice Roberts, Proposed: A Specialized Statutory Immigration Court, 18 San Diego L. Rev. 1, 18 (1980) (the author was the retired Chair of the Board of Immigration Appeals); American Bar Association Commission on Immigration, Reforming the Immigration System: Proposals to Create independence, Fairness, Efficiency, and Professionalism in the Adjudication of Removal Cases, Feb. 2010 and Update 2019, available at. https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/aba-news-archives/2019/03/aba-commission-to-recommend-immigration-reform/(containing more than 100 specific recommendations); AILA, Featured Issue: Immigration Courts, available at, https://www.aila.org/advo-media/issues/all/immigration-courts; Hearing before House Committee on the Judiciary, Courts in Crisis: The State of Judicial Independence and Due Process in U.S. Immigration Courts, Jan. 29.2020, available at, https://judiciary.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=2757; New York City Bar Association, Report on the Independence of the Immigration Courts, Oct. 21, 2020, available at https://www.nycbar.org/member-and-career-services/committees/reports-listing/reports/detail/independence-of-us-immigration-courts. Statement of Immigration Judge A. Ashley Tabbador on behalf of National Association of Immigration Judges before House Committee on the Judiciary, Jan. 29, 2020, available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU01/20200129/110402/HHRG-116-JU01-Wstate-TabaddorA-20200129.pdf. https://www.fedbar.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/19070802-pdf-1.pdf. Other voices include the Roundtable of Former Immigration Judges, law professors (see, e.g., Letter to Attorney General Merrick Garlard, available at, https://www.aila.org/File/Related/21050334a.pdf) and the Marshall Project, Is It Time to Remove Immigration Courts From Presidential Control?, Aug. 28, 2019, available at https://www.themarshallproject.org/2019/08/28/is-it-time-to-remove-immigration-courts-from-presidential-control; Federal Bar Ass’n, Congress Should Establish an Article I Immigration Court, https://www.fedbar.org/government-relations/policy-priorities/article-i-immigration-court/ (last visited May 17, 2021; Mimi Tsankov, Human Rights Are at Risk, ABA Human Rts. Mag., Apr. 20, 2020, available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/immigration/human-rights-at-risk/.

[17] Attorney General Garland has been actively withdrawing decisions issues by his predecessors. See, e.g., Matter of A-C-A-A, 28 I&N Dec. 351 (A.G. 2021), vacating in its entirety Matter of A-C-A-A, I&N Dec. 84 (A.G. 2020) and restoring discretion to IJs in case management; Matter of Cruz Valdez, 28 I&N Dec. 326(A.G. 2021), overruling Matter of Castro-Tum, 27 I&N Dec. 271 (A.G. 2018) and restoring ability of IJs to administratively close cases. These decisions also free up Trial Attorneys to exercise PD.

[18] Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics, available at, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1242156/download (last visited June 1, 2021).

[19] Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics Number of Courtrooms, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1248526/download Data collected as of April 2021).

[20] Executive Office of Immigration Review, Workload and Adjudication Statistics, Tables 25 and 25A, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/workload-and-adjudication-statistics (data collected as of April 21, 2021).

[20] Dept. of Justice, EOIR, Office of the Chief Immigration Judge, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/office-of-the-chief-immigration-judge-bios (last visited May 29, 2021).

[21] TRAC, The State of the Immigration Courts: Trump Leaves Biden 1.3 Million Case Backlog in Immigration Courts, available at, https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/637/.

[22] Memorandum from the Attorney General for the Executive Office of Immigration Review, Renewing Our Commitment to the Timely and Efficient Adjudication of Immigration Cases to Serve the National Interest, Dec. 5, 2017, available at, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/1041196/download.

[23] The total number of pending cases from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras is 715,557. An additional 212, 859 cases from Mexico raise the total to 928,416. Id. at Appendix Table 3. Backlogged Immigration Court Cases and Wait Times by Nationality.

[24] Austin Kocher, ICE Filed Over 100,000 New Cases and Clogged the Courts at the Peak of the Pandemic, Documented, Sept 16, 2020, available at, https://documentedny.com/2020/09/16/ice-filed-over-100000-new-cases-and-clogged-the-courts-in-the-peak-of-the-pandemic/ (last visited May 18, 2021).

[25] Patt Morrison, How the Trump administration is turning judges into ‘prosecutors in a judge’s robe.’ L.A. Times, Aug. 29, 2018., available at, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-ol-patt-morrison-judge-ashley-tabaddor-20180829-htmlstory.html/

[26] Memorandum of James McHenry, Director, Executive Office of Immigration Review, Case Priorities and Performance Metrics, Jan. 17, 2018, available at, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1026721/download.

[27] Matter of Castro-Tum, 27 I. & N. Dec. 271, 272 (A.G. 2018).

[28] U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review (Agency) and National Association of Immigration Judges International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers, Judicial Council 2, 71 FLRA No. 207 (2020).

[29] Amiena Khan & Dorothy Harbeck (IJs), DOJ Tries to Silence the Voice of the Immigration Judges—Again! The Federal Lawyer, Mar.Apr. 2020; available at https://immigrationcourtside.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Immigration-TFL_Mar-Apr2020.pdf; Laila Hlass et al., Let Immigration Judges Speak, Slate, oct. 24, 2019, available at, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/10/immigration-judges-gag-rule.html.

[30] Matter of A-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G.2018) (virtually disqualifying victims of domestic violence and gang violence for asylum). See also, Procedures for Asylum and Withholding of Removal; Credible Fear and Reasonable Fear Review, effective date, Jan. 11, available at 2021https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/12/11/2020-26875/procedures-for-asylum-and-withholding-of-removal-credible-fear-and-reasonable-fear-review.

[31] Executive Office of Immigration Review, Immigration Judge, available at

https://www.justice.gov/legal-careers/job/immigration-judge-16 (last visited May 15, 2021).

[32] IJ Dana Marks provided this unforgettable description on Immigration Courts: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO), Apr. 2, 2018, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9fB0GBwJ2QA&t=11s (last visited May 20, 2021).

[33] These charts were prepared from the biographical information contained in EOIR announcements of new IJs appointed by an Attorney General serving in the Trump administration between May 2017 and April 2021. The government agencies include The Office of Principal Legal Advisor [OPLA] is the prosecution branch of Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE] which in turn is a branch of Department of Homeland Security [DHS]. The Office of Immigration Litigation [OIL], a division of the Department of Justice [DOJ] that represents the government in federal court.

[34] In a picture of the newly installed judges sitting in the New York Immigration Court, 8 of the judges previously worked for immigration enforcement agencies, 3 had represented immigrants and 3 had no prior immigration practice experience. Beth Fertig, Presiding Under Pressure, NY Public Radio, May 29, 2019, available at, https://www.wnyc.org/story/presiding-under-pressure.

[35] Training now is only a few weeks rather than months. Reade Levinson, Kristina Cooke & Mica Rosenberg, Special Report: How Trump administration left indelible mark on U.S. immigration courts, Mar. 8, 2021 (describing inter alia) the selection and abbreviated training processes), available at, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-immigration-trump-court-special-r/special-report-how-trump-administration-left-indelible-mark-on-u-s-immigration-courts-idUSKBN2B0179.

[36] This is not necessarily a new criticism. For example, more than 15 years ago, Judge Richard A. Posner decried “the systematic failure by the judicial officers of the immigration service to provide reasoned analysis for the denial of applications for asylum.” Guchshenkov v. Ashcroft, 366 F. 3d 554, 560 (7th Cir. 2004).

[37] Eighty-two experienced Immigration Judges have resigned since 2017. TRAC Immigration, More Immigration Judges Leaving the Bench, https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/617/. See also Outgoing SF Immigration Judge Blasts. Immigration Court as ‘Soul Crushing,’ Too Close to ICE, S.F. Chronicle, May 19 2021, available at https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/Exclusive-Outgoing-SF-immigration-judge-blasts-16183235.php; Immigration Judges are quitting or retiring early because of Trump, L.A. Times, Jan. 27, 2020, available at, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-01-27/immigration-judges-are-quitting-or-retiring-early-because-of-trump; Why This Burned-Out Immigration Judge Quit Her Job, The Immigration Post, Feb. 27, 2020, available at, https://www.theimmigrationpost.com/why-this-burned-out-immigration-judge-quit-her-job/; Katie Benner, Top Immigration Judge Departs Amid Broader Discontent Over Trump Policies, NY Times, Sept. 13, 2019, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/13/us/politics/immigration-courts-judge.html; Hamed Aleaziz, Being An Immigration Judge Was Their Dream. Under Trump, It Became Untenable, BuzzFeed News, Feb. 13,2019, available at, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/hamedaleaziz/immigration-policy-judge-resign-trump; Ilyce Shugall, Op-Ed, Why I Resigned as an Immigration Judge, L.A.Times, Aug. 4, 2019, available at, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-08-03/immigration-court-judge-asylum-trump-policies.

[38] See, e.g., Statement to the House Judiciary Committee on Immigration Court Reform, Jan. 29, 2020 (36 signers) available at, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU01/20200129/110402/HHRG-116-JU01-20200129-SD022.pdf; Brief for Amici Curiae Former Immigration Judges in Support of Petitioner, Barton v. Barr, 140 U.S. 1142 (2020).

[39] In FY 2020, the denial rate for asylum, withholding or removal or CAT relief increased to 71.6 percent, up from 54.6 percent in FY 2016. 73.7 percent of immigration judge decisions denied asylum. TRAC Immigration, Asylum Denial Rates Continue to Climb, available at https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/630/ (last visited May 116, 2021); see also, Paul Moses & Tim Healy, Here’s Why the Rejection Rate for Asylum Seekers Has Exploded in America’s Largest Immigration Court in NYC, Dec. 2, 2019, available at, https://www.thedailybeast.com/heres-why-the-rejection-rate-for-asylum-seekers-has-exploded-in-americas-largest-immigration-court-in-nyc.

[40] Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics, Asylum Statistics, Data Generated: April 19, 202, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1248491/download

[41] TRAC Immigration, Judge-by-Judge Asylum Decisions in Immigration Courts

FY 2013-2018, available at https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/judge2018/denialrates.html.

[42] TRAC Immigration, Judge-by-Judge Asylum Decisions in Immigration Courts

FY 2015-2020, available at https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/judge2020/denialrates.html

[43] Matter of A-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G.2018).

[44] The Attorney General has the power to certify matters for their review. 8 C.F.R. § 1003.1 (h).

[45] Tanvi Misra, DOJ hiring changes may help Trump’s plan to curb immigration, Roll Call, May 4, 2020, available at, https://www.rollcall.com/2020/05/04/doj-hiring-changes-may-help-trumps-plan-to-curb-immigration; Tanvi Misra, DOJ changed hiring to promote restrictive immigration judges, Roll Call, Oct. 29, 2019, available at, https://www.rollcall.com/2019/10/29/doj-changed-hiring-to-promote-restrictive-immigration-judges/; see James R. McHenry III, Director EOIR, Memorandum for the Attorney General, Immigration Judge and Appellate Immigration Judge Hiring Process , Feb. 19, 2019, available at, https://www.justice.gov/oip/foia-library/general_topics/eoir_hiring_procedures_for_aij/download. The DOJ has been called out in the past for making political appointments during the last Republican administration, see Monica Goodling, et al., Office of the Inspector General, Attorney General, An Investigation of Allegations of Politicized Hiring by Monica Goodling and Other Staff in the, Chapt. 6, Evidence and Analysis: Immigration Judge and Board of Immigration Appeals Member Hiring Decisions, July 2008.

[46] As of January 2020, the lowest starting salary is $138, 630 and ultimately caps at $181,500. Executive Office for Immigration Review, 2020 Immigration Judge Pay Rates, available at,

https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1236526/download.

[47] EOIR, Immigration Judge, https://www.justice.gov/legal-careers/job/immigration-judge-7. This website refers to a section called “How You Will Be Evaluated” which appears nowhere. Military service assures a strong preference.

[48] Jean King, Acting Director, Policy Memo 21-25 Provides EOIR policies regarding the effect of Department of Homeland Security enforcement priorities and initiatives, June 11, 2021.